June 24, 2003

Movies in Context

Jeff Gates proposes organizing a region's movie showings by time instead of theater. It occurred to him because, as a parent, the most relevant piece of info isn't where a film is showing, but when -- because of scheduling a babysitter.

From http://www.copa.org/images/bike/sare.html

Such a system resonates with me, because I'm often in the mood for 'a movie', not necessarily any particular one, and so I'm curious what's starting in the next 30-45 minutes.

It's a common recurrence in design that accommodating a 'special need' provides a solution that ends up supporting a wide range of previously unknown needs. Think curb cuts, which were designed for wheelchair access, but which everyone has likely taken advantage of (on their bikes, rolling handtrucks, etc.). Or OXO's Good Grips line of products, originally designed for people with poor hand coordination, and valued by everyone because, well they're just easier to use.

This is also another argument in favoring of applying faceted classification to, well, everything. In going out to the movies, for most people the film is the most important criterion. For others, it might be a certain neighborhood. And for some, as Jeff shows, it's the timing. The system can never know which particular strategy a given user wants to employ -- so why not avail them of them all?

June 22, 2003

Muy Bueno Muybridge

Ostensibly a biography of Eadward Muybridge, whose motion studies fathered cinema, Rebecca Solnit's River of Shadows is more an historic tapestry of early northern California. Solnit realizes that to chronicle Muybridge's life is to weave together a variety of themes essential to the period (1850s to 1880s), beginning with the notion of "going west" to start afresh, to San Francisco's Barbary Coast mores, linking the continent by rail, incipient environmentalism, and Native American relations.

Additionally, Solnit highlights how a single pursuit, Leland Stanford's 1878 commission of Muybridge's earliest motion studies, spawned two themes which would become essential to California in the following century. The most obvious theme is that of motion pictures, the defining industry of southern California. Second, and probably with more impact, Stanford's patronage was perhaps the first serious pursuit of technological research in the young state, a precursor to the Silicon Valley which would grow around Stanford's greatest legacy, the university that bears his name.

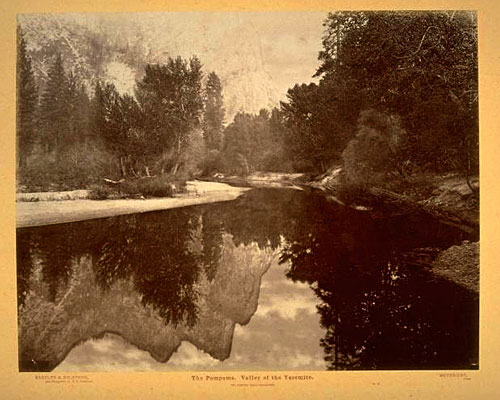

The Pompoms. Valley of the Yosemite. The Jumping Frogs Reflected. No. 13.

As a film history dilettante, I'd already been well aware of Muybridge's motion work. What particularly intrigued me was learning of his earlier landscape efforts, including a set of mammoth (20" x 24") photos he took of Yosemite, including the one above. These pictures are available through the Bancroft Library and are definitely worth perusing.

Pigeon flying, from http://photo.ucr.edu/photographers/muybridge/index755.html

Perhaps Solnit's most illuminating, and most frustrating, chapter is her last. Muybridge is dead, and she demonstrates the dominoes that subsequently toppled, leading to the motion picture industry and Silicon Valley. A valiant effort, it's too much for just one chapter--there's enough material for at least one book. Still, it's a minor blemish in an otherwise captivating work that ought to resonate with many in California.

As a final note, it wasn't until I read this book that I made the connection between Muybridge's multiple camera set-up, each of which took a single shot so as to later simulate real motion, and the multiple camera set-up used to created the "Bullet Time" effect in The Matrix, each of which shoots film in order to create unreal slow motion.

Actually, this will be the final final note. One last impression I received from the book was how, not so long ago, "art" and "science" (or "technology") weren't really considered distinct discilpines. People just did what they did, and if it advanced art, great, and if it advanced science, great.

Woman pouring a bucket of water over another woman 1884-85, taken from here

Okay, I lied, this is the final note. Long time peterme readers know I used to write a lot about comics, spurred in large part by Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics. It turns out, as demonstrated by the picture above, that Muybridge was a proto-photo-comics artist. His motion studies often contained simple narratives, meant to be 'read' when finally published.

June 19, 2003

Themes in User Experience, Part III - Emotion in Business

At the DUX 2003 conference, I found myself on a panel talking about organizational and business issues. I was substituting for Jeff, who was unable to attend.

It was a great panel -- each panelist presented ways they were able to get folks in their organizations to appreciate user-centered design. After the panelists spoke, I realized a thread emerging about the value of emotional pulls. Bill Bachman from Adobe used "UI Trivia Quizzes" and report cards to make smart interface design less dull, more engaging. Steve Sato found that a CD with video of customer visits and usability tests, "[engaged colleagues] at an emotional level that is rarely touched by logic alone." Jeff had found a similar response when showing tests of the usability of PBS' member stations. Jan-Christoph Zoels showed beautiful design prototypes of washing machines that hinted at compelling future possibilities.

It was surprising, on what was essentially the "business panel" for touchy-feely emotions to keep cropping up. There's a tendency to assume that business is driven by numbers, and in talking to most user experience folks about their difficulties in work with 'business', the primary issue is a lack of good metrics.

This panel showed that metrics is only part of the picture. You need to compel others viscerally as well. It reminded me of a comment my partner Janice made in her workshop on "Managing Design Politics" -- people use their intellect to rationalize a decision already made through emotion.

June 15, 2003

That Tricky Word, "Design"

Appropos of the DUX 2003 conference, I've found myself grappling with my relationship to the word "design." It came to a head on the Tuesday following the conference, when I participated in a panel recapping what had happened. Before it began, I was chatting with co-panelist Hugh Dubberly, and mentioned that in the next iteration of the Adaptive Path website, we will not refer to our work as "user experience design," and are in fact moving away from the word "design" altogether.

What's wrong with "design"? Well, there's nothing wrong with the practice, but plenty wrong with the word's associations. Right now, particularly in the field of web user experience, the word "design", without a modifier, means visual design. Adaptive Path doesn't perform visual design services (though we love partnering with those who do). But, more importantly for us, "design" has been relegated to the world of tactics. "Design" is what happens after the strategy has been settled, the specifications determined, the raison d'etre developed.

This is unfortunate. Design, with a capital D, ought to stretch beyond tactics, and into strategy. Design methods are brilliantly suited to figuring out WHAT to make, not just HOW to make it. I find Herbert Simon's definition apt: "Everyone designs who devise courses of action

aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones. The intellectual activity that produces material artifacts is no different fundamentally from the one that prescribes remedies for a sick patient or the one that devises a new sales plan for a company or a social welfare policy for a state."

However, I see no need to be a champion for the cause of "design." When we hired a consultant to help us reposition our marketing, she had two concerns -- the phrase "user experience" and the word "design." The former concerned her because it's jargon-y, requires definition, and often gets confused with user interface. The latter because she sees the word design in our marketplace being used by firms that don't do what we do, and that we do what they don't do. While we're willing to fight the "user experience" fight, because we feel we can help define it, fighting the "design" fight simply doesn't interest us.

Again, not that we don't do design. Information architecture and interaction design are valuable kinds of design. Even the strategies we craft could be considered 'design'. But, I don't think we're wedded to the term 'design.' None of us went to design school. We don't feel the need to be associated with the word. In fact, we find that potential clients see "design" as a commodity, somewhat interchangeable, and not understanding its true value, often go with the less expensive option.

(For what it's worth, I think pretty much the exact same thing about "usability" as I do "design" -- it's tactical, and quite possibly, even *more* of a commodity. But writing about the term 'usability' would have to be the subject of a whole other post.)

June 14, 2003

Up with Down With Love

It's disappointing, but not surprising that Down With Love is doing such mediocre boxoffice.

I caught it at the Parkway last night, and, well, I'm hazarding a guess that the film is simply too weird for most moviegoers. The movie is pure confection from start to finish, taking its Manhattan 1962 setting and running with it delightfully. It's beautiful and fun to look at. David Hyde Pierce gets to do some wonderful bits of business. Renee Zellweger is, naturally, cute-as-a-button. The story borders on meaningless, but that doesn't matter -- this is a comedy, and there are plenty of laughs and smiles. The film remains self-aware from start to finish, but never smugly so -- you're invited in on the fun, not made to feel condescended to.

Peyton Reed displays a remarkably confident directorial hand, and this is a worthy follow-up to his surprisingly good prior effort, Bring It On. Given his arch sensibility, I'm curious as to what he'll make of The Fantastic Four.

June 05, 2003

Themes in User Experience, Part 2: Empathy

A long time ago, I wrote that "non-empathic geeks become engineers, and empathic geeks become information designers." Empathy is a critical quality for people working in the user experience field. We've developed numerous tools, from contextual inquiry to usability testing, to help us get inside the heads of the people who will be using our systems.

Through our empathy, we inevitably become advocates for our users. When people in the organization try to get end-users to do things they would have no reasonable interest in doing, we pipe up, saying, "You can't expect people to do that! They have no motivation for it, there's no value in it for them!" When people in the organization dismiss those who can't use a product as "stupid users", we shout, "They're not stupid! They're just being people! They're being themselves. You haven't bothered to understand the context in which they're using it, their capabilities, their desires. Don't call them 'stupid'!"

And then we often turn around, and complain about those "stupid engineers" or "stupid marketers" or "stupid management." They don't understand anything. They're just making our jobs harder.

It's a little ironic, no?

In the last couple of years, pretty much since starting Adaptive Path, I've realized that we user experience types need to expand our empathy beyond our end-users, and to include our colleagues (or clients) as well. It's surprising how willing we are to deal with the idiosyncracies of our user population, and yet so unwilling to really understand the perspectives of those we work with--Why they make certain decisions, what pressures and motivations they have, because of whatever means by which they are measured.

If we dismiss our colleagues and clients, they will dismiss our efforts. All designers have had the experience of their designs not seeing the light of day. And, in my experience, that's largely due to the designers focusing solely on their processes and their users, and not aware of the internal realities in which this design must take root.

The empathy we show our users helps make our designs better... But if we want to make sure our designs get implemented and get out in the world, then we need empathy for our colleagues.