January 31, 2004

Designing for People - Chapter 5: Through the Back Door, Chapter 6: Rise in the Level of Public Taste

For the sake of completeness, I'm addressing these two chapters, but not in as much depth as the others. This is where Dreyfuss is weakest, and exposes a certain time-boundedness. Chapter 5 attempts to boil down art and design history in three pages -- but it's so cursory that I suspect the veracity of his history. He puts forth that industrial designers weren't able to bring their new, functionalist aesthetic in through the front door, because it conflicted too much with contemporary styles, but it worked through the back door, because in the kitchen, bathroom, and laundry, "utility transcended tradition."

Chapter 6 defends the aesthetic taste of Americans. Dreyfuss puts forth a populist notion of the masses now able to appreciate good design thanks to modern production and design. He also (unwisely) goes on and on about how American people have awakened to fine art, classical music (as evidenced by the success of symphonies on television!), and theater. What Dreyfuss couldn't have known in 1955 (or could he?) is that while television may have seemed a cultural panacea in 1955, it wouldn't take long for its higher aspirations to be dashed on the rocks of a more crass commercialism and appeal.

Where this chapter succeeds is in pointing out how designers draw from a variety of sources to inform their approaches, aesthetics, and ideas. Historic forms demonstrate that which has survived through the ages, and probably with good reason. The experimentation of avant-garde creators "gives us courage to try new forms, techniques, and materials."

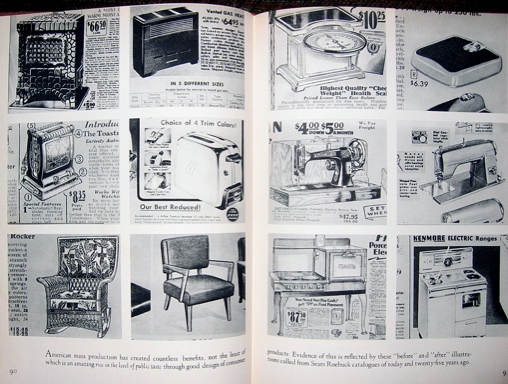

Dreyfuss relates an experience he had, presenting to Dutch product manufacturers how to appeal to American tastes. Cognizant of the language barrier, Dreyfuss found a visual solution: he juxtaposed images of products from a Sears Roebuck catalog, contrasting 25 years prior with the contemporary designs.

This exercise encourages me to consider "before" and "after" designs of website home pages. While hardly the best measure of the evolution of design approaches and tastes, it would provide a glimpse. At some point, I'll main the Wayback machine. But to continue...

While it took Don Norman about 15 years from the publishing of The Design of Everyday Things to acknowledge the importance of aesthetics and emotional appeal in design, Dreyfuss understood the impact of appearance:

...I am convinced that a well-set dinner table will aid the flow of gastric juices; that a well-lighted and planned classroom is conducive to study; that carefull selected colors chosen with an eye to psychological influence will develop better and more lucrative work habits for the man at the machine....I believe that man achieves his tallest measure of serenity when surrounded by beauty...

January 29, 2004

Designing for People - Chapter 4: The Importance of Testing

This is the one chapter which will likely induce the most forehead-slapping for any practicing user-centered designer. Because it points out that, 'lo those many years ago, Henry Dreyfuss practiced a form of usability testing in order to understand how well his designs were performing. Those of us who have had to fight to get things tested will wonder how on earth such a situation can still exist, considering leading designers were testing half a century ago.

One of the crucial elements of Dreyfuss' testing is that, while rigorous in set-up, it was also informal in its practice. He didn't get hung up on some desire for scientific accuracy in his testing -- he just wanted to see people use his designs, understand what worked, what didn't, and be able to revise accordingly. It's something of a shame that the human factors world has so promoted a "right" way of doing usability that it has lead many people to feel that such testing can only be done by a Ph.D. In my experience, such folks often don't get the true value of testing in a design process, which is simply as a reality and sanity check, not as some attempt to capture 95% of all errors.

Dreyfuss recognizes that simply asking preferences from people can be misleading (hello, focus groups!), as they'll tell you what they think you want to hear. You've got to try to get them to *behave* as naturally as possible. He also highlights that other common pitfall -- the client claiming to do research, or to understand the customer, when, in fact, well, they don't.

Dreyfuss encourages as much _in situ_ observation as possible. That can be hard for us who work with computer interfaces -- there's not a lot of opportunity to watch people use them, and even when there is, say at a laptop-filled coffeehouse, folks aren't really appreciative of you staring over their shoulders. That said, I always find it fascinating to watch my parents at the machine, or my girlfriend as she surfs the Web. It reminds you just how different people can approach this similar box in different ways.

Dreyfuss details ambitious testing environments: a to-scale set of completely furnished rooms for an ocean liner, built in an old stable; or an interior mock-up or an airliner, complete with staff. In the latter they had "passengers" in the mockup for ten hours (the time of a transoceanic flight in those days).

The chapter ends with some amusing tales of perceived affordances in early airplane experiences:

I'll reiterate his final sentence:

At the expense of forfeiting originality, and it is a great temptation to hide locks and access panels, we try to make things obvious to operate, not only in airplane interiors, but in everything we do.

And he's talking about physical objects with inherently more obvious affordances! It still mystifies me, how many "designers" seek to obscure interactive elements to serve some aesthetic desire (and they often proclaim the value of "discovery" in the experience. Feh.)

January 28, 2004

Four Corners Then and Now

Back on our southwest road trip, we stopped at the Navajo Fry Bread National Monument.

Actually, it's the Four Corners National Monument, which is on Navajo land, and at which we spent more time waiting for and eating fry bread than we did viewing the monument.

Anyway, my parents dug up a picture of me at the same site 23 years earlier.

Designing for People - Chapter 3: How The Designer Works

In this chapter, Dreyfuss lays out his process for designing products. What's most intriguing is how what he writes is pretty much a summary of the two-day workshop my company teaches on design methodology. Everything old is new again.

The best overview is this photo spread showing how they addressed the design of a new vacuum cleaner for Hoover.

He discusses the need to meet with stakeholders, to conduct a competitive analysis, to understand the capabilities of the equipment, and to begin with sketches and then iterate the design in increasing levels of fidelity.

He stresses developing a close co-operation with the engineers, and how they're able to utilize the same common denominator -- Joe and Josephine. What was that about how personas can help an entire team rally behind a design goal?

Dreyfuss designs for the complete customer experience:

If the product is to be packaged, we design the conatiner, carton, and price tag. Occasionally we have designed the truck that delivers it. We interest ourselves in these matters because they complement the product. In certain merchandise they create the invaluable first impression in the mind of the customer which leads to ultimate purchase.

Dreyfuss points out that in the early days of industrial design, engineers regarded designers as "intruder[s] who [were] after their jobs." I can say that, without reservation, the same is true in the early days of information architecture and user experience design.

He also allows himself to grouses about the term "industrial design."

The word "design" is certainly not the exclusive property of the industrial designer. Its dictionary meaning, "to contrive for a purpose," makes it equally the property of engineers, architects, advertising men, artists, and dressmakers. The qualifying word "industrial" doesn't pin it down precisely either. But it's too late to try to coin a substitute..

As someone who has watched his profession generate a lot of heat, and little light, around terminologies and definitions, I think we ought to follow Dreyfuss' lead, and just accept it and move on.

There are two points he addresses that I think user experience folk would do well to heed. The first is the tight co-operation between designers and engineers. In my experience, this pretty much doesn't occur. Design and engineering is mediated by product management, who hand the specifications developed by designers to the engineers, and that's pretty much that. Back in the olden days, when I was a wee web developer, I made sure to work closely with designers so that they knew the capabilities of the web medium -- it's limitations and its opportunities. This collaboration lead to innovative solutions that truly took advantage of the medium. It's sad this this approach seems to have, by and large, fallen by the wayside, as companies wall-off their various disciplines.

The second point he addresses is for the designer to develop ever-more-high-fidelity models. In my experience, this, too, doesn't happen. Interaction designers come up with wireframes. Visual designers create final "looking" designs. But these are all static creations.

We get closer when we prototype in HTML, and perhaps even closer when we use JavaScript to 'fake' server-side interactivity. But we really ought to strive for prototype environments that are fed real-live actual data, but which still maintain the flexibility and iteratibility of HTML markup.

January 27, 2004

IS212: Information in Society Reading List

A course I'm planning on auditing this semester (schedule willing) is Prof van House's class on Information in Society. And my desire to sit in was bolstered by looking over her reading list, which includes direct links to the material (as opposed to just pointers to books you can buy).