August 29, 2004

People Are The Same The World Over

I've just completed the first section of Lawrence Weschler's delightful collection of essays, Vermeer in Bosnia. One essay, "Aristotle in Belgrade", follows protests in the face of rigged elections. He describes the Serbian political mindset as being able to support seeming opposites -- "they could simultaneously feel that their neighbors were affording them no threat and exult at a visiting demagogue's promise that he wasn't going to let those neighbors 'beat you anymore,'"" -- and of not being cognizant of consequences -- "They saw no problem in roundly despising a leader and simultaneously planning to vote for him."

Weschler explains the origin of such puzzling thought as "state propoganda, [which] had blithely spewed forth all manner of contradictory positions simultaneously." His tone, however, is a bit condescending -- as if it's a Serbian problem that he just cannot understand.

I read that passage the day I read Louis Menand's piece in the latest New Yorker, "The Unpolitical Animal." It's a roundly depressing piece, filled with evidence that people make political decisions without the slightest concern for ideology, issues, and consequence. I'll quote the passage that connected me to Weschler's work:

Repeal [of the estate tax, which effects the wealthiest two percent of the populations] is supported by sixty-six per cent of people who believe that the income gap between the richest and the poorest Americans has increased in recent decades, and that this is a bad thing. And it’s supported by sixty-eight per cent of people who say that the rich pay too little in taxes. Most Americans simply do not make a connection between tax policy and the over-all economic condition of the country.

Americans are, clearly, just as contradictory as Weschler's Serbs. I suspect Weschler's condescension toward the Serbian mindset has likely lifted, given an editorial he penned for the LA Times, "He's The Picture of Racial Compassion," about how President Bush employs photos of himself with black people in an attempt to demonstrate his "compassion" toward them, though his policies have only served to hurt them.

Weschler is the head of the New York Institute for the Humanities at NYU, though it's not clear that the institute actually does anything.

He's also trying to get a magazine titled Omnivore off the ground.

And the Globe and Mail has a decent interview with Weschler.

Jumping through hoops

A while back I posted about how product designs are getting too difficult, and how the greater the number of steps it takes for someone to set up a product, or to use a service, the less successful they will be. In it, I mentioned the Six Sigma concept of Rolled Throughput Yield: "the probability of being able to pass a unit of product or service through the entire process defect-free."

Let's say you have a website, and a registration process that takes four steps. Each step is pretty well-designed-- 90% of users are able to complete each step. However, only 65% of people will actually make it through, because you're losing people every step of the way (.9 x 4 = .65). The shows that often the best way to address the problem is not to improve the individual elements, but to remove elements altogether.

More recently, I wrote about how hard it is for organizations to produce well-designed products, because in order for a good design get out in the world, it has to run jump through a set of departmental hoops -- be approved by the business owners, marketers, designers, engineers, manufacturers, etc. etc. At each step, the project can be stalled. Or so many people have to be pleased, products are "designed by committee" - not a recipe for innovation.

This struck me as a kind of organizational variant to Rolled Throughput Yield. Particularly because we've seen that the organizations that do support innovative design have smaller, multi-disciplinary teams, not departmental stovepipes. It also struck me that these are two sides of the same coin. The complexity of product from the first example is often a result of the complexity of organizations in the second -- design by committee, or some form of serial design process, leads to products with too many discrete parts and interfaces, which are essentially invitations for something to go wrong.

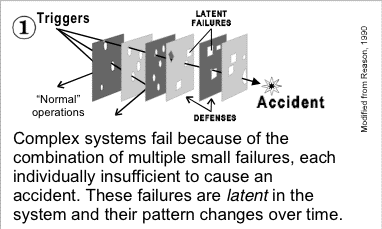

Separately, on a bit of a Googlewander, I came across David Woods, who, among other things, has written about "human error."In reading some papers he wrote on the topic, I came across this diagram:

Taken from here (PDF), which is meant to be read in conjunction with this (PDF).

(I've been meaning to read more of David's stuff for a while. I think the study of "human error" can be an insightful perspective for user-centered design.)

The challenge, of course, seems to be to manage complexity. Complexity seems to be a given. Is it? Is increasing complexity inevitable? Occasionally products emerge that massively reduce complexity (at least, complexity of use), and are popular -- the original Palm (compared to earlier pen-based computing) and Google come to mind. Maybe the iPod (I don't know how it stacks up to other music players from a complexity standpoint).