December 13, 2005

Notes from User Interfaces for Physical Spaces

Yesterday I attended User Interfaces for Physical Spaces, a one-day workshop and field trip co-produced by MAYA Design and the IA Institute. The day was essentially an extended case study of the work MAYA did with the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh (the public library system, CLP), applying methods of user-centered design and information architecture to the design of physical spaces.

The story of how the project landed at MAYA was illuminating. The CLP planned for major architectural renovations to their main library and branches. They sent out an RFP to a number of architecture firms. They awarded the project to EDGE design, because their proposal included their stories of trying to *use* the library (and struggling). EDGE developed a vision for a modern library, including information displays and kiosks. MAYA was originally brought in to help with the interactive portions of the system, but when they asked EDGE and the CLP what went on the kiosks, no one had a good answer. MAYA realized they needed to step back and truly appreciate the space.

In MAYA's Office

The bulk of the workshop took place in MAYA's offices, where we walked through the development of their designs. MAYA's first project was a 6-week-long intervention, with discussions with key CLP staff, guerrilla on-site research, development of key personas of library users, scenarios of use, and the development of a framework for understanding the entire system of use.With their scenarios, they identified four components in this process: Users (1) go through Organizers (2) to get Materials/Activities (3) in order to Use/Participate (4).

This is a pretty standard process for smart user-centered design, but there was a key point of differentiation from screen-based work. It comes with what MAYA calls Organizers. MAYA identified three classes of organizers -- Library Staff, the Physical Space, and the Categorizations in the catalog system.

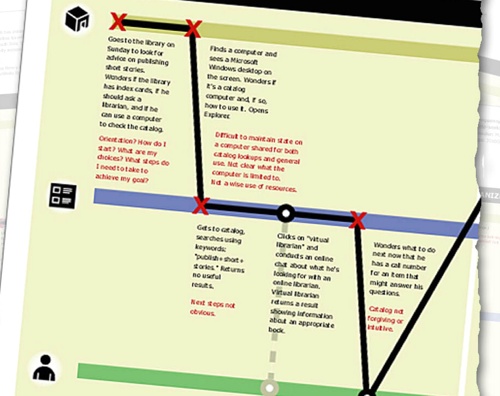

MAYA developed scenarios of use for their four key personas, and through that identified breakpoints -- moments where a person's attempt at getting something done is stopped by some problem they run into.

Initial attempts at diagramming the scenarios linearly went nowhere, but thinking through the problem, they realized the breakpoints mapped to the organizers -- things broke down when switching from people to categorizations, or from the categorizations to the space.

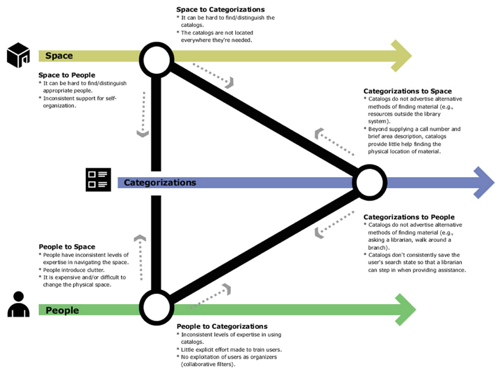

The A-ha! moment for them came in this distinguishing these organizers, because it led to the development of a framework that allowed them to get their head around the problem. The realized that the primary problems people had in using the library occurred when people switched from organizer to organizer -- from using the online catalog to engaging with the space, or from talking to a librarian to using the catalog.

This also served as an A-ha! For the CLP. Up to this point, MAYA was essentially telling them what they already knew -- there was a myriad of problems people face when using the libraries. The framework allowed the CLP to better understand the problem space.

So, unlike screen-based work, where we tend to get caught up in breakpoints with a single "organizer" -- the software -- MAYA had to grapple with three potential points of failure. This is orders of magnitude more complex.

This triangle shows what needs to be considered when handing off from organizer to organizer before the breakpoints occur -- and to smooth those handoffs by being aware of the issues that arise when making those leaps.

The 6 week project ended with "Tiger Teams" of 4 or 5 folks -- designers and CLP staff -- rapidly prototyping solutions to accommodate this new understanding. These blue sky propositions were meant to encapsulate the research in an explicit fashion -- not just giving the CLP a bunch of documents with models on them, but ideas for the implications of these findings on design.

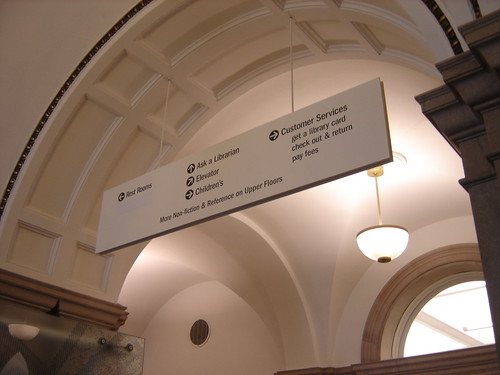

After the 6 week project ended, the CLP asked MAYA to help develop an actual solution for the library. This involved, essentially, in developing an information architecture that tied together the three organizers. They overlaid this information architecture on the physical architecture, by annotating actual building blueprints. They spent a lot of time refining nomenclature for wayfinding (thus arriving at "Ask A Librarian" instead of "Reference Desk" or "Customer Services" instead of "Circulation Desk"), and they worked closely with Landesberg Design to develop a signage system that communicated this information architecture clearly.

Field Trip!

After walking through MAYA's process, we then boarded a chartered school bus (really! yellow on the outside! green canvas seats!), and headed to some renovated libraries. The first library was the Squirrel Hill branch.

Squirrel Hill residents, though, know just how difficult the old library was, and dearly love their new space. It's clearly become a true community center -- people hanging out, reading, surfing the internet (free wi-fi!), and connecting with one another.

Photo by James Melzer

The second library we visited was the Main Library. This library has a host of complications, the biggest of which is that it's in an 1895 building on the register of historic places. This meant that it's boxy, room-to-room-to-room layout couldn't be changed.

Still, the Main library had some important successes. The Cafe is extremely popular, and its yellow floor has become a point of reference for wayfinding.

They've also been able to incorporate much of the signage and language that worked so well in Squirrel Hill.

The Main Library also demonstrates what happens when there is too much architect-intervention. Each library is modified by a different architect. At Squirrel Hill, the architect was content to pretty much follow the plan, and create an inviting, open space that just worked. At the Main, the architect did very well to open up and brighten the space, but often missed the point when it came to wayfinding.

Whereas the wayfinding system designed for the libraries involved white type on black, at the Main, they used the more traditional black type on white. Unfortunately, white is everywhere (all walls were wisely painted white to improve the lighting), and that means the signs get lost in the sea of white.

Also, the architects seemed to have a fetish for glass panels. Glass walls are everywhere in the new library, whether it makes sense or not. Perhaps the most egregious case is above the librarian desk near the entrance. While you can see the "ask a librarian" sign if you're staring at it straight on:

...when you shift your angle, it pretty much disappears:

It's fascinating to me the way that designers simply won't leave well enough alone. Actually, well make well enough worse by fiddling with it.

Well, this was a great event, and a huge thanks to MAYA for opening their doors, and the work, up to others.

Urban walking - musin' on cruisin'

The chapters I'm reading in Wanderlust dwell on urban walking. Solnit points out that, in the early 1800s, walking around cities was quite the daring affair.

Perhaps, not surprisingly, it brought to mind some of the seamier experiences I've had on foot. This is probably true for every peripatetic male -- at some point, you will be cruised.

End of the Innocence

The first time it happened, I was 12 or 13. I was hanging out at the Santa Monica Pier, playing video games. I had with me a copy of Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, which I planned to read as I walked the mile-and-a-half home.

As I walked up the ramp that connects the pier with the city of Santa Monica, I was joined by a skinny mustachioed guy, probably in his late 20s or early 30s. I remember seeing him down in the arcade, where I didn't think anything of it. Being somewhat oblivious (well, and 12 or 13), I didn't think much of it as he struck up a conversation with me.

It didn't occur to me to do anything other than converse with him. So, as we're heading down Ocean Ave., we're talking about lord knows what, when he invites me to his trailer to play video games. He had an Atari or Colecovision or something (this would have been 1985 or sp), and his trailer or whatever he lived in was parked in the lot next to the RAND corporation.

Well, it was at this point that I realized what was going on. I didn't make a scene out of it -- in fact, the conversation kept me from boredom. I rebuffed his offer, though he was dogged in sweetening the deal (and if memory serves, that might have been literal -- he might have talked about candy he had).

After about a mile, as I was turning down 3rd Street to head home, this guy realized he wasn't getting anywhere, and peeled off. I read my book the rest of the way home, and told my parents what happened. They were, more than anything, bemused.

Beantown Buggery

A more recent incident happened a couple years ago in Boston. I had been hanging out near downtown, and as dusk turned to dark, I decided to walk back to my hotel in Cambridge. There's a park along the Charles River that leads to a bridge.

Walking in the park, a man on a bicycle heads toward me. I must have made eye contact, because he promptly stopped, turned around, got off his bike, and walked with me. Unlike my youthful experience, this was far more... direct and ribald. I don't remember exactly how the conversation unfolded, but in short order he claimed a 9-inch penis and that he was quite good with otherwise straight men.

I professed my disinterest from the word Go, but he was persistent, striding alongside me for, I don't know, half a mile or so. Finally he realized he was wasting effort, got on his bike, and departed.

As I crossed the bridge, I called Stacy (back in the Bay Area) to tell her what happened. "Guess what, honey! I was cruised by a guy with a 9 inch dick!" She wanted to know if I had actually seen proof, and I had to admit that I hadn't. You mean, that guy might have been lying?