September 20, 2003

Urban Tribes: A scathing book review

A potentially important sociological trend is developing -- more and more people are deferring marriage until later and later in their lives. The period between "college" and a "new family" continues to grow wider. Likely the product of the social and civil reforms of the 60s and 70s, this large sector of single, college-educated, professionals deserves study; it could have significant impact on a society and an economy that are geared more towards marriage and raising families. Somebody should write a book about this emerging force, who they are, where they came from, and where they're going.

Unfortunately, Urban Tribes is not that book. I first wrote about urban tribes almost a year a half ago, when I came across a web site promoting the book, which was then very much a work in progress. My post inspired some discussion in the comments. A couple of months ago, the book's author, Ethan Watters, emailed me, having stumbled upon my blog post, and asked if I'd be interested in reading an advance copy of the book. I said yes.

Considering such interest and generosity, I was really hoping to like the book. However, I cannot in good conscience recommend it. The book's one strength is calling attention to an important emerging trend. However, Ethan's handling of the topic left me very disappointed.

The bulk of the book is a pastiche of Ethan's memoir about his own urban tribe and anecdotes from people who wrote to him about their urban tribes. Both the memoir and the anecdotes are dull, and their suitability for this topic are questionable. If you're writing about an emerging social trend, you've got to get beyond individual's stories and relate the underlying patterns and data that support your thesis.

If you're going to take the memoir and anecdote approach, then you better have some riveting tales to tell. The prose in Urban Tribes is slack, whether it's Ethan navelgazing about his experiences in an urban tribe (okay, fine, you were known as being a dating disaster, let's move on), or the superficial anecdotal quotes from those who wrote to him. I

Also, when addressing a new concept, it doesn't hurt to define what it is that you're talking about. I now know about Ethan's trips to Burning Man, but I still haven't read a satisfactory definition of an urban tribe.

Sprinkled around the edges are brief mentions sociological data about urban tribes, and some references to academic researchers who say stuff that he thinks is interesting in the light of urban tribes. Such allusions carry little weight, so I left the book wondering if Ethan has spotted what is truly a significant trend, or if it's just a small vocal group of people who think their particular life situation is f-a-s-c-i-n-a-t-i-n-g.

I guess what upsets me most is this book seems lazy. His work biography says he's a magazine writer, but I guess that's not the same as a journalist. The bulk of his information comes from his own uninteresting life or from stuff emailed to him. His few attempts at getting out there, such as when he flies to Philadelphia to witness an urban tribe, fall flat when he realizes there's little he can draw from his observations.

Where the book most shamefully falls down is placing the "urban tribe" within any larger context of social trends. The urban tribe is likely a result of social changes of the 60s and 70s. I would guess that the burgeoning equality of women is the paramount influence. In addition, the American economy has evolved such that it's economically more challenging to be married with kids. In the past, a single wage-earner could buy a house and support a family. Nowadays, both parents must work to keep up. Faced with such a prospect, is it no wonder that folks aren't rushing into such a costly lifestyle?

Ethan offers no sociological perspecive though, instead just returning again and again to the notion that "in the past" we were "supposed" to get married right out of college, and these days we don't seem to be doing that.

And, regrettably, there's no looking forward. What does the larger group of "never-married"s mean to a society that promotes marriage? What are the economic implications of larger numbers of successful careerist singles, earning sizable salaries with no one to spend it on but themselves? Don't look to Urban Tribes for any answers.

If this critique is harsh, it's because I think a rich and worthwhile opportunity has been summarily wasted. This topic needs a journalist, or a sociologist, someone to dig through the data, the research. Someone to conduct their own studies to probe unanswered questions. Someone to situate this within other parallel social trends (fewer children per family, growing numbers of the aged, etc.). Someone to explore, ethnographically, the makeup of urban tribes, the roles within, and to relate the stories from these groups in a compelling fashion. I suspect that book is being worked on as I write this review. I look forward to reading it.

September 14, 2003

Conference Keynote - Inspiration from Visual Models of User Research

I've been invited to give the keynote at the upcoming About, With and For Conference, October 17 and 18 at IIT's Institute of Design in Chicago.

The conference invites folks from business, design (isn't design part of business?), and social sciences to discuss methods for synthesizing user research. They've put together a top-notch list of speakers, (which makes me wonder how a young turk such as myself is giving the keynote!). And it's pretty cheap, as conferences go (the highest price is $200).

In my presentation, I'll be discussing models we've developed at Adaptive Path for synthesizing user research (such as the mental model described in this case study). However, I realized I didn't want this to be just about the work I've done. I wanted to place these efforts in an historical context, both within HCI and from a range of disciplines that have developed methods for analyzing observed or inferred human behavior.

Human Behavior Models in HCI

For me, the standard-bearers of HCI modeling are Hugh Beyer and Karen Holtzblatt, whose various work models are, I believe, the backbone of their contextual design methodology. I attended their class at CHI '98, and light bulbs went off when I saw how they turned mushy user research data into solid models from which you could design.

An excellent reproduction of the models from Beyer and Holtzblatt's book can be found here.

On another note, I would be remiss if I didn't mention Alan Cooper's work with personas and scenarios. Though not diagrammatic, they serve the purpose of distilling observations into a form you could then utilize in design -- the persona.

Archaeologists Analyze the Past

One place I've found some interesting diagrammatic analyses is in the field of archaeology. Archaeologist James Deetz turned the discipline upside-down with his seminal essay, Death's Head, Cherub, Urn and Willow, which charted the stylistic evolution of gravestones in colonial New England. There are two depictions of note. The first is the "battleship" diagram, showing popularity of styles over time:

Never before had such a statistical representation been brought to bear on material culture over time. As Deetz asks later in the essay, "what does this mean in terms of culture change? Why should death's heads be popular at all, and what cultural factors were responsible for their disappearance and subsequent rise of the cherub design?" These are the kinds of questions opened up once you witness the data in this synthesized form.

The second clever representation depicts the branching trees in the stylistic evolution:

Though this doesn't have the simple classic qualities of the battleship diagram (it's wedded to its context, whereas the battleship could be applied to any number of situations), it assists in analysis of the subject.

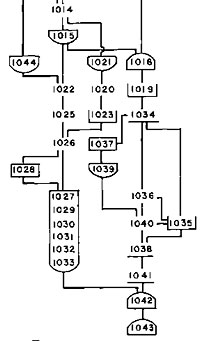

Another archaeological analytical model is the Harris Matrix. Developed to understand complex stratigraphy in big digs, it's a boxes-and-arrows system that will seem familiar to any information architect.

I won't get into details, but suffice to say that boxes represent different layers, and that the older layers are beneath the newer layers. As an Harris Matrix evolves, it not only helps archaeologists make sense of what they're seeing (and make sure they keep things in the right order), it eventually becomes a tool by which others, even those who aren't archaeologists, can understand what is happening underground.

Analyzing what humans have left behind makes me wonder if similar models will begin to make sense as we build a record of what humans have done online.

Social Network Analysis - The Socio-Gram

Another group that's developed an interesting model for considering human behavior or social network analysts. Which makes sense -- it's hard to understand a social network without some boiled-down depiction of it.

I've written about SNA in the past, and won't repeat myself here.

Anyway, one reason I'm posting all this is to see if you good people who read my blathering have other examples of systems of synthesis of observed human behavior that would make a good subject in such a talk. I have to imagine that sociologists, anthropologists, psychologists, cognitive scientists, business people, anyone who has to consider what people do and make sense of it in some fashion, have their own ways of depicting such analyses. Pointers?