I was asked to speak at UX Week 2012, and figured I’d turn my blog post “User experience is strategy, not design” into a talk, but a funny thing happened along the way. I realized that, yes, UX is design, but not design as we’ve been thinking of it. And by reframing “UX design” as a profession, we can set it up to uniquely address increasingly prevalent business needs.

Before tackling the profession, we need to agree on just what “UX design” is. I have not come across a better definition than Jesse’s, which he originally shared in 2009:

Experience design is the design of anything, independent of medium, or across media, with human experience as an explicit outcome, and human engagement as an explicit goal.

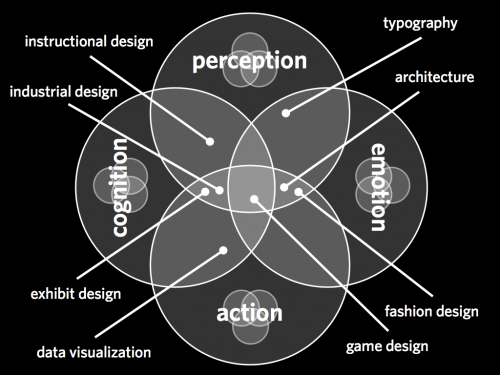

Jesse went on to define human engagement across four factors — perception, action, cognition, and emotion, and then showed how design contributes to this engagement:

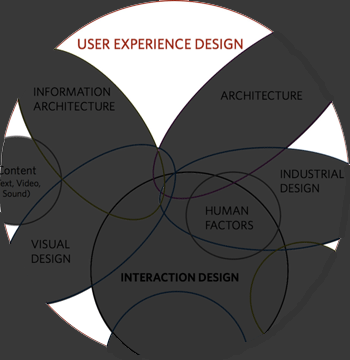

Similarly, Dan Saffer attempted to diagram the scope of user experience design:

These both present very broad mandates. This is particularly vexing for those who see design as execution, as making stuff, Because how can anyone be expected to execute on all that? How can UX design as a profession address the enormity of what it encompasses?

And I think the issue is that we haven’t been able to see the forest for the trees. UX design isn’t all of those disciplines. UX design is not design-as-execution. UX design is what’s left.

What’s more, Jesse’s and Dan’s diagrams are overly design-oriented. User experience arises from the sum total of interactions with a organization’s products and services. If we take Jesse’s definition to heart, we need to recognize that just because UX emerged from software and grew on the web, that doesn’t mean it has to be digital. User experience is affected by business development, marketing, engineering, customer service, retail, as well as product and service design.

An analogous model for UX design

The challenge for the UX designer is to identify where, how, and at what level to engage in order to appropriately address this scope. Typical “UX design”– workflows and wireframes– is insufficient. It needs to embrace a much broader potential that drives outcomes through deep organizational engagement.

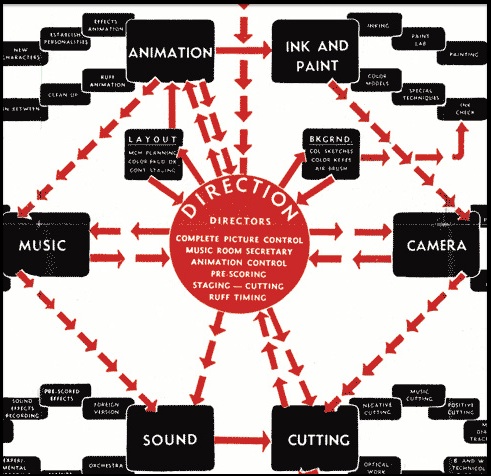

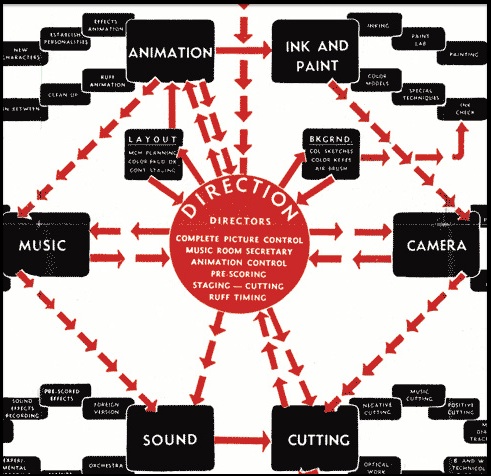

I propose that we think of UX design in a manner similar to film direction. To explain what I mean, look at this org chart from Walt Disney (I’ve zoomed in on the pertinent area).

A film director doesn’t “do” anything. All of the execution is carried out by specific craftspeople. The job of the director is to coordinate, to orchestrate these activities in order to deliver on a singular vision. The director likely came up through a specific craft (writing, acting, editing, cinematography), but through experience and vision, has come to lead across all these functions.

I propose that the profession of the UX Designer is analogous to the profession of the film director, coordinating across all those disciplines identified in the diagrams (and undoubtedly other activities).

(It’s worth calling out that Dan mentioned something similar in the post supporting his diagram, but he was somewhat dismissive about the role of the creative director, saying there wasn’t much to it, and that it was a temporary role.)

What this means is that UX Designer is not a workflows-and-wireframes role. It’s a leadership role (though not necessarily a management role). It is a systems role — UX brings humanity to systems design and engineering. UX is a fundamentally synthetic role, not just coordinating these distinct activities, but helping realize a whole that is greater than the sum of the parts. And while a UX Designer uses design approaches, they are not for typical design outcomes.

So, what does this person do?

The UX Designer doesn’t sit in a chair and shout “action!” (Actually, neither does the director. That’s usually what an assistant director does.) In order to support the orchestration of organizational resources to deliver great experiences, there are a set of activities I see UX designers leading.

User Insights

At the heart of great user experience is a deep understanding of the user, and the UX Designer should lead the development of insights that will help a company deliver better experiences. I’m calling out “user insights” distinct from “user research” — not all user insights are gleaned from user research, nor should the UX Designer necessarily be the user research lead. If user research is being conducted, the UX Designer should make sure to understand it well enough to be able to understand and prioritize the insights which will subsequently drive the design and development work.

Ideation and Concept Generation

Driven by user insights and other sources of inspiration, the UX Designer leads the team in coming up with ideas and concepts to address user’s behaviors, motivations, and context. There are many ways this can happen — sketching, brainstorming, bodystorming, improv, prototyping. The UX Designer identifies the most productive approaches, and then, as ideas emerge, filters out the less effective ones, and helps refine and evolve the great ones.

Experience strategy and vision

Perhaps the single most important responsibility for the UX Designer is to develop a clear experience strategy, and craft a compelling vision. An experience strategy specifies how a product or service will be successful from the perspective of user experience. A common part of experience strategy are design principles that help drive decision making.

Essential to helping a team understand how to realize an experience strategy is the creation of an experience vision. An experience vision provides a ‘north star’ for the product development team, helping them understand where they’re heading, and inspiring them to get there. These often take the form of prototypes — my favorite experience vision is Deborah Adler’s masters thesis for a new kind of pill bottle, dubbed SafeRX, which lead directly to Target’s ClearRX. I’ve had some success with illustrated scenarios of future experiences (either hand-drawn, or photographed). “Concept videos” inevitably seem like overkill and are usually never worth it.

Experience planning

It’s not sufficient to simply have a vision. And it’s typically not feasible, nor desirable to hold out on launching something until the complete vision can be realized. A UX Designer develops a plan for how to get from a current state to this desired future. What are in V1, V2, V3 along the way to the promised V4? Brandon’s Cake Model of Product Strategy shows how experience planning differs from typical product planning, because of its insistence on something experientially desirable at each stage.

Team Facilitation

While a visionary and a leader, the UX Designer must be a strong facilitator as well. There’s no way one person is going to have all the best ideas, so it’s up to the UX Designer to get the best from a broad, cross-functional team. Facilitation is less a discrete activity than a responsibility throughout a project. There will be a lot of things activities to facilitate, including branding exercises, customer value proposition articulation, tangible futures, and ideation and concept generation.

Oversight and coordination

This is the ongoing making-it-real of the experience strategy and vision. The UX Designer engages throughout the entire process, and makes sure that the user experience is never being compromised. If circumstances arise that force changes, the UX Designer leads the discussion to make sure that the new solution still adheres to the overall strategy. The UX Designer must sweat every detail, and, yes, occasionally be a jerk about it. As Charles Eames said, “The details are not the details. They make the design.”

What does this all mean?

My call for making the UX profession a strategic, planning, and coordinating one is not original. Here’s how Donald Norman, who coined “user experience” as we now think of it, framed it in 1995:

We describe the role of the “User Experience Architect’s Office”, which works across the divisions, helping to harmonize the human interface and industrial design process across the divisions of Apple and ATG.

The need Don recognized 17 years ago not only still remains, but is far more acute. As we’ve shifted from a world of standalone products to one of connected services, the increased complexity only makes poorer experiences likelier to arise.

Most people calling themselves “UX Designers” are not. They are interaction designers and information architects. These are perfectly laudable practices in their own right, but if “UX Design” is going to contribute meaningfully in this connected world, it can no longer be bound up in the constituent disciplines from which it emerged, but instead must embrace a new mandate to ensure the delivery of great user experiences regardless of where those experiences take place.